J Balvin and I have a date at Tiffany’s.

Admittedly, even I don’t realize this until I reach the storied display windows on Fifth Avenue, where I’m led to a private elevator manned by a uniformed attendant who silently takes me up, up, up. The doors open to a stunning private room with unfettered views of the Manhattan skyline and Central Park — where I also find José Álvaro Osorio Balvin himself. He looks every bit the lord of the manor, in a casually elegant short-sleeved white T-shirt tucked into sleek black Prada cargo pants. His beard is trimmed and his hair is pulled back in neat cornrows, exposing the matching diamond studs in his earlobes. On his wrist is a Patek Philippe watch.

It’s a rare oasis of calm for an artist who lately seems to have been moving nonstop in multiple directions at once. Since the beginning of the year, Balvin has appeared in the cinematic teaser for Usher’s Super Bowl halftime show; released a new shoe in collaboration with Air Jordan; been the face of Cheetos’ new “Deja tu Huella” campaign; performed a major Coachella set (the second-highest billed artist of the day, behind Doja Cat), featuring a surprise appearance by Will Smith; toured Europe and then Australia and New Zealand; and in August, released Rayo, his first album since 2021. He’s currently preparing a collaboration with G-SHOCK watches. Before the year is over, Peacock will broadcast a new interview series he’ll host. And he’s already gearing up for his first feature film lead role, in the drug drama Little Lorraine, helmed by Grammy Award-winning director Andy Hines and planned for a 2025 release.

It’s a remarkably fruitful time — both creatively and commercially — for the Colombian star who three years ago, during the pandemic and at the height of his popularity, saw public opinion in some quarters turn sharply against him after a rapid-fire series of unfortunate, almost surreal incidents.

In 2021, following the birth of his son Rio (with his longtime girlfriend, model Valentina Ferrer), Balvin found himself in the crosshairs of rapper Residente, who took umbrage with Balvin’s call to boycott the Latin Grammys due to the absence of reggaetón in the main categories and who posted several scathing videos chastising him on social media.

Not long after, Balvin was criticized for his portrayal of women in the video for his 2021 song “Perra,” an edgy collaboration with Tokischa. Directed by Raymi Paulus, Tokischa’s collaborator, it showed Tokischa, who identifies as a queer woman, eating from a dog bowl and Balvin walking two Black women dressed as dogs on leashes, prompting Colombia’s then-vice president, Marta Lucía Ramírez, to call out the song’s “misogynist lyrics that violate women’s rights, comparing them to animals.” Days later, Balvin apologized publicly and removed the video from YouTube.

Mere weeks after that, confused fans questioned why the 2021 African Entertainment Awards named Balvin Afro-Latino artist of the year. “I am not Afro-Latino,” Balvin posted to his Instagram story in Spanish. “But thank you for giving me a place in the contribution to Afrobeat music and its movement.”

Then, in March 2022, Residente, whom Balvin had considered a friend, resurfaced with “Residente: Bzrp Music Sessions, Vol. 49,” a no-holds-barred, nine-minute opus made with Argentine DJ Bizarrap that torpedoed reggaetón in general but zeroed in on Balvin, criticizing him for, among other things, “using mental health to sell a documentary” and for the “Perra” video.

And through it all, Balvin’s mother was in and out of intensive care in the singer’s native Medellín. (She is now better but still has health struggles.)

While Balvin kept up with social media posts and appearances, privately he was taken aback. “In my entire career, I had never been a person who had scandals,” notes the 39-year-old, who says he hasn’t spoken to Residente since. “I used to say, ‘Why do all these artists have things happen to them, and nothing happens to me!’ You’re looking at it from up there, and then, suddenly you’re in the middle of it.”

Musically, Balvin went quiet — mostly — for nearly three years. An extraordinarily prolific artist, between 2014 and 2021 he had released six albums, all top 10s on Billboard’s Top Latin Albums chart, including four No. 1s, and charted 96 singles on Hot Latin Songs (including nine No. 1s) and 18 on the Billboard Hot 100, including the chart-topper “I Like It,” with Cardi B and Bad Bunny. (Balvin also holds the record for most No. 1s on Latin Airplay, 36.) After March 2022, he put out only a handful of singles and no albums.

But Balvin, a relentless hustler at heart, regrouped with his family; parted ways with Scooter Braun, who had managed him during this turbulent period; and took stock of his friendships. During this dark hour, he sought advice from Maluma, a colleague who had never been a close friend, but who had experienced similar public excoriation in 2016 when he released his controversial song “Cuatro Babys.”

“I was always very willing to help José when all this happened because I went through that,” Maluma says. “At end of the day, even if you pretend it doesn’t matter, it hurts when people have the wrong idea about you, and defending yourself against the entire world is very difficult. Plus, we’re both Colombian, we’ve both had beautiful careers, and we’ve elevated our country and our genre. José is one of the most important pillars of Latin and urban music. He takes his career very seriously. It was the least I could do.”

Entire Studios top.

David Needleman

Balvin began to formulate a plan for returning to the spotlight. He approached Roc Nation co-founder and longtime CEO Jay Brown, and two years ago, signed with Roc Nation to manage all aspects of his career. “He was being very thoughtful about what he wanted. He was looking for insights on how to grow his brands, how to expand on what he wanted to do with his career, outside his music,” Brown says, noting that he and Balvin communicate almost daily. “It’s about managing his enthusiasm, his inspiration. He loves what he does, he loves touching people, he loves being out there. I think that’s refreshing. And he’s a good guy. It’s hard to say no to something like that.”

In 2022, Balvin launched his education-focused foundation, Vibra en Alta, in Colombia. Earlier this year, he also switched labels, moving within the Universal family from Universal Music Latino to Capitol under Capitol Music Group chairman/CEO Tom March and Interscope Capitol Labels Group executive vp Nir Seroussi, a good friend. At the same time, he returned to the studio, working with longtime producers like Jeremy Ayala (Daddy Yankee’s son) and Luis Ángel O’Neill, while also trying out new material with young, rising artists like Saiko, Dei V and Feid.

In short order, he cut more than 40 tracks, which he then narrowed down to 15 spunky reggaetón bangers for an album he named Rayo, which translates to “lightning.” The name and the sleek, silver car on the cover pay homage to Balvin’s first car, a beat-up red Volkswagen Golf that he drove to gigs — a hopeful symbol of all the possibilities before him.

“I wanted to focus on the clear comeback of a Balvin focused on music, his career and his legacy,” Seroussi says. “When I sat down with him to see where he was spiritually, I saw a José that is going to win. He wakes up in the morning as if he were a new artist.”

Four months ago, Balvin wrote me on WhatsApp. He was ready to talk, he said, about everything. And so, here I am high above Tiffany & Co. for a private afternoon of coffee and macarons — just the two of us. As we chat, his openness surprises me. But then again, as Seroussi says, “He’s an artist who has nothing else to prove, but wants to keep doing music. Every [Latin] artist today who has something to do with urban music at a global scale can in some way trace back to what José opened for them.”

Balvin will sit down for a live one on one interview during Billboard Latin Music Week. You can purchase your tickets here.

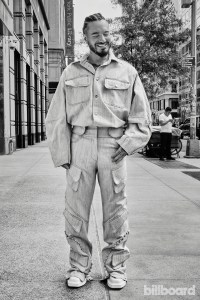

Luar jacket and pants, Vetements shoes.

David Needleman

Your son Rio was born at a hectic point in your life. What did his arrival mean to you at the time?

His arrival was perfection because having Rio at that moment allowed me to really focus my energy on a person who came to bring me light. It was as if God was saying, “OK, I sent you a trial, but here’s a gift.” And I say that because since Rio’s birth, my — how do I say this — my emotional intelligence has grown very much. I don’t remember losing control since my son’s birth. I’ve had complicated moments, but I’ve never lost control. He brought me strength, a lot of patience, but yes, a lot of light. In fact, I made the Jordan Rios — which are black but have a sunset in the sole — based on the fact that in a moment of darkness, my son came and brought me light.

Let’s talk about this moment of darkness. It became really complicated for you on many fronts, particularly your dispute with Residente.

Have you ever had a friend turn on you? I considered him a friend, and I spoke with him as if he were a friend. Very openly. Con mucha confianza. That’s what surprised me and hurt and opened my eyes. I still believe I can make new friends, but it’s a little more complicated finding them these days. Because some of the people I thought were my friends ended up not being that. Obviously, this happened, it’s done, I’ve matured and I’m not holding a grudge or anything like that. I had to forgive myself for being so naive and opening my heart so easily to some people. The toughest part was to encounter a dark side of humanity in a moment of darkness. And I’m not saying I’m the most illuminated person either; I’ve made mistakes, and maybe I’ve made friends feel bad. But I’ve never betrayed a friend.

Personally, I never found you offensive. How do you think you made people feel bad?

I’ve been very honest. But as a paisa, we’re jokesters and we can get out of hand, and not everyone understands. We’re very open, and other cultures sometimes don’t understand that and take it the wrong way.

Feuds are common in rap and reggaetón. But this felt more like an attack than a feud. You never replied to Residente’s dis track, did you?

Never. First of all, you need to know what court to play in, right? When all this happened, it was the most complicated moment for my mom’s health. She was in intensive care. She told me, “Promise me you won’t reply and you won’t say anything. Do it for me. I know you, I know your essence, and this isn’t for you.” And the weight of a mother’s word is everything.

Is she aware of these things that happened to you?

Of course. And my mom suffered a lot. Now that I’m a father, I understand. It’s crossing a powerful line. A line that’s family, it’s sacred. The pain caused to a mother, a family, a sister, to the people who love you, was complicated. And it was complex for me because, following my mother’s advice, I never spoke out about this and I never defended myself. But I’m very clear on who I am. I’m not going to go out there and explain who I am to the world because clearly, people who know me know my essence and those are the people I want to be in good standing with.

I think not replying was wise…

As one of the leaders of Colombia’s movement I can’t set a bad example, no matter what people would like to see. I’ve always strived to be a better person and a gentleman in life. Being a decent person is a much harder task than being an “artist,” [which is] easier in the sense that if you have a talent and patience, you’ll get there. But being a better person is a daily task.

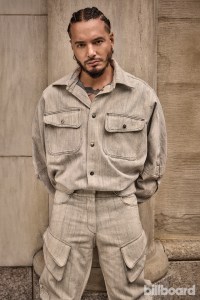

J Balvin photographed August 20, 2024 in New York. Entire Studios shirt.

David Needleman

You also had an issue surrounding the video for “Perra,” your single with Tokischa.

I’ve always been known for supporting new talent, and in Tokischa, I saw a woman who was very empowered and daring and who spoke positively about her sexuality in a way I had never seen before [in the Latin world], like Nicki Minaj or Cardi B do here in the U.S. If men in reggaetón can speak about their sexuality this way, I was struck to see a woman doing it. My mission was simply to do what I could to elevate and promote Tokischa and her art to a wider audience. I respect the way each person wants to conceptualize their vision, and this was her vision and her creation. I went there to support her vision, and I paid dearly for it.

In this case, after many people criticized the video, you not only took it down from your YouTube channel, but you spoke out and gave a public apology. Why?

I spoke out because this was a much deeper issue in that it went into topics like race, masculinity and machismo. However, if people had listened to the song, they would have realized it’s a story that has nothing to do with going against a race or gender. It was totally the opposite. Tokischa is an Afro Latina woman, and she was representing her race, her culture and the idiosyncrasies of her world. And obviously, my lyrics, I always approach them in a very commercial way and I’m very careful about what I say. But when things happen, they happen all at once.

I know you went to Maluma for advice. What did he say?

Maluma and I weren’t really friends. We were colleagues, but we also competed with each other. But I wrote him, and then I sat down with him. We’ve become very close. I’ve come to appreciate him and respect him more than ever, and now I can say he’s like a younger brother to me. I imagine it must have been tough when things happened to him, but then you grow an armor. That’s what happened to me. I became very cold; I didn’t want to open my heart to anyone. When I went back on social media, I didn’t want to go back to the old José who’s always making jokes and teasing, because I had a mental block. Until Rayo came around and I started to make music again for the love of music 100% and stopped thinking about the business.

How was your approach different?

I began to make music with a sense of security that came down to: I don’t have to prove myself in this business. It would have been complicated if I hadn’t achieved anything [before] and I had to prove myself. But we’ve achieved so many changes and evolutions. I remember you interviewed me years ago with Nicky Jam and you asked: Do you think a song in Spanish will make it to No. 1 on the Hot 100? And I said yes.

I remember that conversation well. And it happened.

We unlocked that. We unlocked performing at the Super Bowl. We unlocked having the most streamed artist in the world, we unlocked the first stadium played by a solo reggaetón artist, we unlocked sneaker culture, fashion, Guinness Records, so many things that hadn’t happened before. So I kind of look back and say, “Prove what? I need to regain my confidence after all these blows and enjoy the process.”

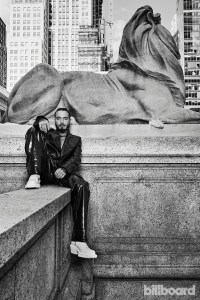

Luar jacket and pants.

David Needleman

You didn’t release an album for three years. For you, that’s an eternity…

And during those three years, I never left the top 50 of the most streamed artists in the world [on Spotify, where Balvin ranked No. 31 at press time]. It’s a beautiful thing to see that in a business where so few artists have the luxury of even saying, “I’m taking a year off.” Obviously, I questioned myself a lot when I came back. “Why the f–k did I leave?” Although I never stopped working. I kept playing festivals in Europe and all that. But I think my official return was when I played Coachella.

I have to imagine that setting foot on that Coachella stage was a little nerve-racking.

Of course! Plus, that show was planned for a year because Coachella had never allowed something to be hung from the roof, because of the wind in the desert. So we took the risk of hanging the [giant inflatable] UFO, and the investment was very high. But it was finally spectacular, and having Will Smith [make a guest appearance to perform “Men in Black”] was very cool. I saw myself in him, in the sense that both of us went through a dark period — and I know that mistakes don’t define a person and can’t detract from the greatness of what he’s achieved. I was so happy to share his return because after the Oscars incident, this was his first public appearance, and a week later, Bad Boys [for Life] came out. And it wasn’t planned!

Were you two friends?

No, we had never met. I [felt] I needed something else to really make a statement in the show. And Will Smith came to mind, because what’s better than Men in Black? [Balvin reached out to Smith’s team and ultimately FaceTimed him.] I told him my mission, with my passion. He said, “Give me a week.” [While I waited] like a good, hardworking paisa, I sent him a photo of the Virgin [Mary] praying. Then I sent him a votive candle, as if I were praying; then a voodoo doll. And exactly a week later, he called and said, “Let’s do it.”

Following Coachella, you took your tour to Europe, Australia and New Zealand to play for big and very receptive crowds despite these regions not being your core markets. Was that gratifying for you after a traumatic period?

When I did that tour, [and when] I went to Medellín to release the album and I saw the euphoria among the fans, I thought, “It was all in my head.”

Entire Studios top and pants, Air Jordan 3 x J Balvin shoes.

David Needleman

You’ve achieved global domination in many spheres. Most recently, you became the artist with the most titles, 15, in YouTube’s Billion Views Club. What drives you today?

What’s most important is a super reconnection and a super service to my Latinos, 100%. They’re the foundation of everything. The reason I’m a global artist is because Latins gave me that power. And I want a super reconnection with new generations and Gen Z. It’s never been a problem for me to connect with new generations because I like new artists and I enjoy collaborating with them. From there, I’d like to do a grand tour of the U.S. and Latin America. And I want to unlock India. Unlock it completely.

You were perhaps the first major Latin artist to talk frankly about mental health and your struggles with it. I know this has been a journey for you and you’ve taken medication for anxiety at times.

I still do. Always. Some people can do without meds. In my case, they’ve been lowering the dosage and I haven’t had any issues since my son was born. None. That’s why I said before, in the darkest moments, I didn’t lose control. But I take my pills daily. It’s perfectly normal, as if someone had an issue with high [blood] pressure. But there’s also meditation — I’ve been meditating since I was 19 years old — daily exercise, eating habits and the people you surround yourself with. The fact that I don’t do drugs or anything like that has also been part of having that mental, spiritual balance.

What role has Colombia’s music scene played in exposing the country to the world?

Music has been a path of light for Colombia at a global scale. I think it saved an entire generation. Now, all these Gen Zers want to be artists instead of drug dealers or killers for hire. When I started in music, there wasn’t a map for urban music in Colombia. There was Shakira and Carlos Vives and Juanes, but they were completely different genres. [Daddy] Yankee inspired me, but he’s Puerto Rican. No one had globalized urban music from Colombia. We literally took a pick and an axe and paved the way. I don’t know how we did it, but we did. And now I see this whole new generation of artists, like Ryan Castro, Blessd.

Karol G has also been steadfastly by your side. In fact, she invited you to perform at one of her shows at MetLife Stadium in New Jersey last year…

Karol is a friend who’s also become a teacher. That was a beautiful moment here at [MetLife] to come together again in a stadium full of people who came to see her. I told her, “You used to look up at me, and now, I’m your biggest fan.” It’s a beautiful cycle and I’m so proud of Colombia. We’re a small country but so strong in our music.

Luar jacket and pants, Vetements shoes.

David Needleman

How do you see yourself today?

I value what I’ve achieved, without a doubt. The insecurity I felt has gone, and I feel like a brand-new artist. If you listen to Rayo, you hear a refreshed J Balvin who had a good time. I didn’t make this album thinking I was going to make an album. I went to make music and remembered how I felt when I was 19 years old and I just wanted to show every song I made to my mom, my sister, my girlfriend, my friends. That’s why, when I finished the album, I wanted to name it for that moment in time, when my only ambitions were artistic, when I really knew nothing about the business.

You really feel like a new artist?

One hundred percent. And I’m working like a new artist. I mean, most artists of my level don’t go to Mexico and sit down for 200 interviews. I do, and also, it’s been three years! I’m ready to be overexposed. Whatever I need to do, it’s Balvin time. And I say that with certainty and because I know what I have and what I can give. Something positive always happens when I give it my all. I went through the dark times, and now, the sun is out and it’s shining on my face.

At 39 years old, how do you feel about longevity?

I’ll perform and record as long as I’m happy and people connect with me. We have yet to see the first elder reggaetón artist. We have the OGs — Yandel, Wisin — who look great. Yankee looks younger than when he started. But honestly, we haven’t had the example of seeing how long a reggaetón artist can go for. I see myself super gangster in the future. Not evil gangster, but as someone who’s done well, who’s been strategic in his movements and has done something well for society and culture. Like a Latin Jay-Z.

This story appears in the Sept. 28, 2024, issue of Billboard.