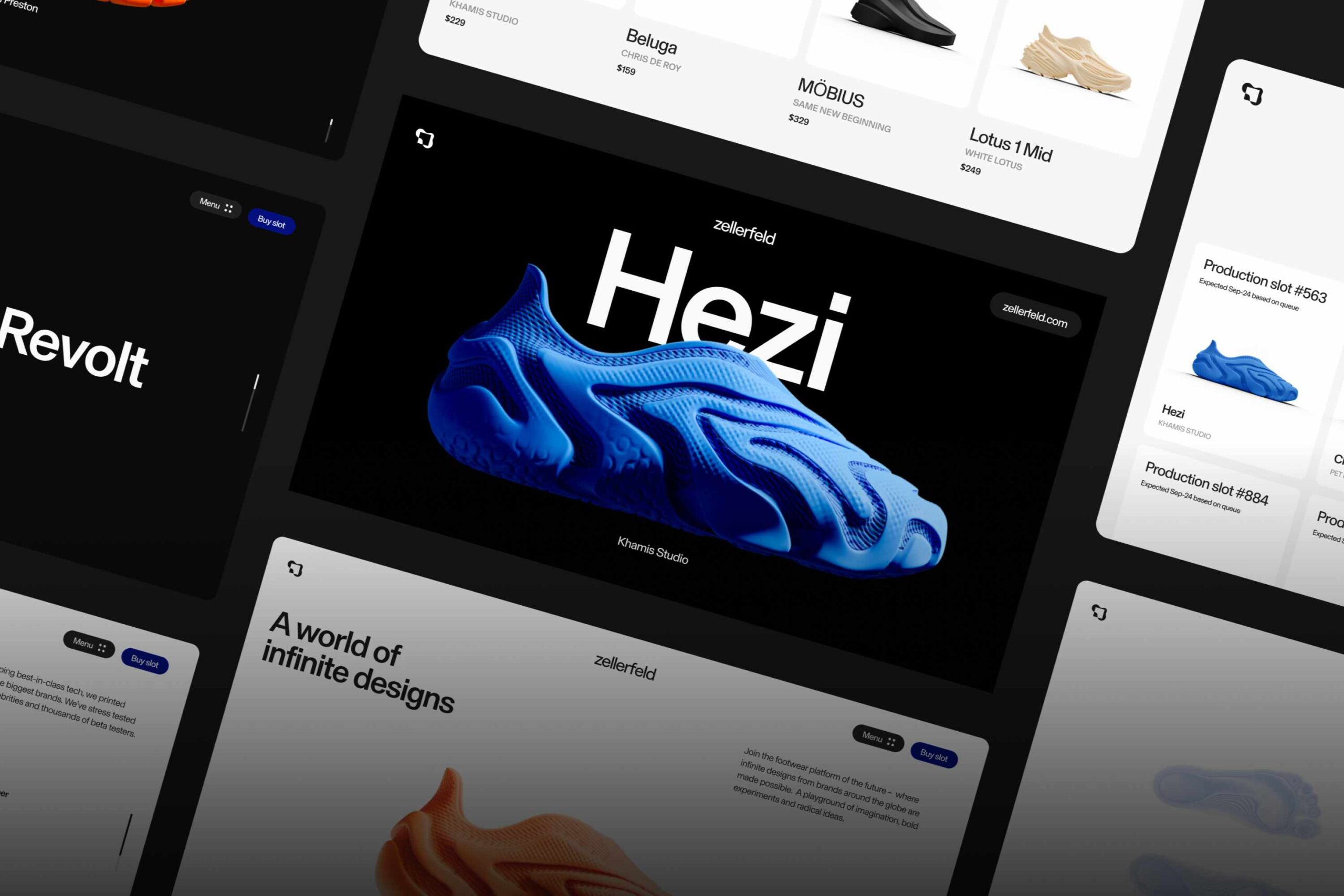

You might know Zellerfeld for 3D-printing sneakers for luxury labels as disparate as Moncler, Heron Preston, Kidsuper, Louis Vuitton and even YEEZY. Zellerfeld would rather you know it for creating what it’s calling the “YouTube of shoes,” part of the upstart’s greater “war in the footwear industry.”

I spoke with Zellerfeld’s excitable CEO, Cornelius Schmitt, in a video call prior to the June 25 launch of an open-source tool on Zellerfeld’s website that it promises will democratize sneaker design.

Schmitt bounced around, showing off some truly impressive sneaker designs made using Zellerfeld’s dynamic 3D-printing tech, shoes that looked at once familiar but entirely alien.

There was a chunky sandal created by Christophe De Roy, the guy who designed the YEEZY Slide for adidas, for instance, but also a wild slip-on envisioned by 3D-printing footwear auteur Benjometry, its shape formed with AI.

All of the shoes are laceless, hard-wearing — Zellerfeld promises two years of wear per foam shoe, at least — and designed to fit each wearer’s foot.

Would-be Zellerfeld customers need only send the company a tracing of their foot and its machines will hone each 3D-printed sneaker to the customer’s exact podiatric dimensions.

Not only does this create a literally seamless shape for maximum comfort, it also renders laces redundant, a point enthusiastically underlined by Schmitt, who cheerfully raved about “the end of laces” slipped on a tall boot for demonstrative purposes, bending the squishy silhouette with ease.

These are, to be clear, snug shoes, made of a material that delicately wraps the foot in plush softness. Imagine Crocs’ cushioning but as a holistic shoe; no blisters here.

The biggest benefit that Zellerfeld promises, however, goes beyond the shoes themselves. Indeed, it sees this as the total leveling of the footwear playing field.

Its new tool not only allows users to design and create their own made-to-order shoes, but profit from them, fulfilling a power-to-the-people pledge illustrated when this sort of tech first got going.

In a nutshell, you’ll pay Zellerfeld a flat fee for the real-world creation of your 3D-printed sneaker.

You can simply create a one-off shoe for yourself or make the completed design available for anyone to purchase from Zellerfeld’s website. Any time anyone else purchases your shoe — shaped to their foot dimensions, of course — you receive royalties, the same privilege afforded to famous folks who partner with the sportswear giants on collaborative or signature shoes.

However, unlike those mainstream propositions that’re only relegated to the ultra-famous, Zellerfeld’s self-described “YouTube of shoes” will distribute heightened payouts to its participants.

Schmitt laid out a conventional scheme wherein a big-time third-party collaborator might receive, at most, 15 percent from each sneaker sold from their partnership with an international sneaker giant. That’s business as usual.

Zellerfeld, however, is granting users 60 percent of the profits from each shoe sold. Think about it: if your $200 Zellerfeld sneaker is purchased 1,000 times, you’d receive about $120,000 in gross royalties.

That’s Zellerfeld’s upshot.

There are some wrinkles, like realities of fabrication — Zellerfeld encourages would-be sneaker entrepreneurs to pay $10 for a place in its production queue — and limitations of the tech. For instance, though Zellerfeld sneakers can replicate a variety of textures and weights, they can only be printed in single hues for now. A multitude of combo colors and patterns are in development.

Zellerfeld aims to win the “war in the footwear industry” by giving users the ability to create their own perfect shoes in perpetuity. Certainly, the promise is there: the number of foam slip-ons and slides worn every day is evidence that consumers have little issue giving up laces and organic materials like suede.

But will the sneaker-shopping world so readily abandon all of its conventions for alien shoes that hardly resemble the sneakers of old? Is this, as Schmitt claims, 3D-printing’s Amazon moment, wherein an upstart challenger uproots all the old stalwarts with unforeseen access?

It will certainly be comfortable, at least.